“Could you make a sand drawing of a Land Rover Defender 1km wide?” asked a chap I would soon know so well called Ross Pinnock.

I have a habit of agreeing to things that I don’t yet know how to do but am confident we can work out. I have a little saying that ‘Jamie of the future who has to work this out will not be happy with Jamie of the past who so casually agreed to it.’

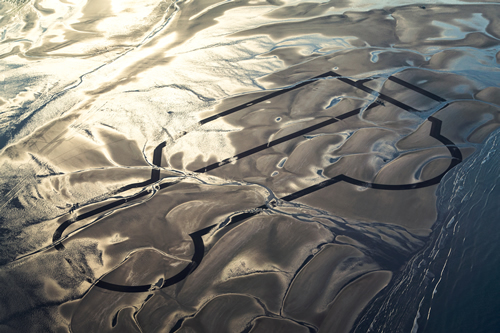

Sand drawing is a mission. It takes planning, teamwork and nigh on perfect execution. When Land Rover asked Sand In Your Eye to lead an operation to draw a Defender in the sand of Red Wharf Bay on Anglesey, where it was first conceived by Maurice Wilks 68 years ago, they handed me and my team one of our biggest ever challenges. The sheer scale of the endeavor was awesome. A kilometre wide by 500 metres high, using six different models of Land Rover to create it. From one end of the drawing to the other you wouldn’t even see a person, you would barely be able to see a Land Rover!

Usually with sand drawings, you get a window of about five to eight hours between tides to complete them. It’s immediate, intense, exciting work. In this case, the lack of daylight hours meant that we had between three and four hours before sunset. Often when you put a team to a task, if you run out of time people will muck in and work late to get the job done. With sand drawing there’s none of that. You’ve got a window, if you don’t get it done, the tide’s going to come in and wash away your half-finished image. You have your parameters and you’ve got to deliver. The pressure is on. There is no overtime.

A beach is such a dynamic environment. You’re working with a canvas that is changing every day. When the tide recedes, you can never be absolutely sure if the water will drain away. One of our biggest challenges was Red Wharf Bay itself. It really isn’t a good place to attempt something like this. It’s full of pools of water and from the sky you can see a texture of streams running through it. There is even a river on the left of the beach that has quicksand, so we had to work with the Maritime Office to identify the best spots. If you try to rake wet sand, your lines simply vanish. When we researched Red Wharf Bay, we actually asked Ross and Land Rover if we could use another beach, somewhere else on Anglesey with well-drained sand flats. Of course, they said it had to be here. This is where the first concept of a Land Rover was drawn in the sand. Stephen Wilks, the son of Maurice Wilks described the reason:

“My father drew an outline in the sand of how he thought the Land Rover could be made. It was originally a plan to use the Rover factory production line until they could get more cars off it, and the aluminium body was in response to the shortage of steel after the war. But the design took off. From then on we would come here every summer and ride to the beach in a Land Rover. Its silhouette riding over the sands was always recognisable at a distance. It is an iconic design.”

So what followed was weeks of planning on how to make an image 1 kilometre wide in a few hours on a beach full of standing water and tidal streams. We worked out various methods of which we settled on one. This required Tom Bolland and I to spend countless hours designing and checking our strategy. If you saw us some time in September running around fields or jogging on the beach of Red Wharf Bay seemingly aimlessly, then that is what we were doing. I also got to play with a Defender on the beach to check our methods. I drew a childlike doodle in the sand, the picture was naive but the lines the Defender left were formidable and much more distinctive than left by a rake. A couple of aerial shots confirmed that it could actually work. So we agreed to take up the challenge.

When the day came on the 7th October, the whole project was a little overwhelming and some people asked what is the point as the image is ready to be erased as soon as it is finished? Aside from the amazing photography, I think the point is that the people who were there on that day experienced something special together. I couldn’t just rock up on a beach myself and do that. It takes a coordinated team working well together to actually achieve something like this. We had people from really different backgrounds – artists from Sand In Your Eye, technicians, drivers, filmmakers, photographers, even the guy doing the catering. Everyone has a vital part to play. The result is not only the image itself, but also the achievement of doing it.

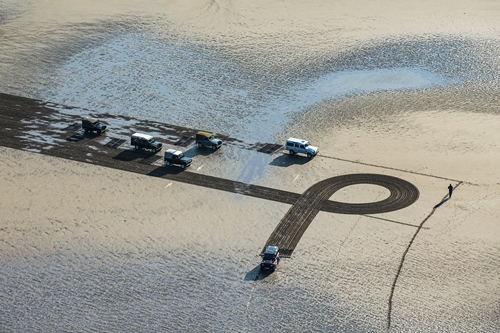

So in the morning we watched as the sea gradually descended down the beach partially revealing the sand. This was our cue. The Sand In Your Eye team jumped in two land rovers and we drove out over what seemed like an endless beach to meet the sea. The Land Rovers then left us with a wheelbarrow, some rakes, a couple of binoculars and we were on our own, isolated from the rest of the world. The sky meeting the sea, the sound of the waves making themselves heard, “We may be going out now, but we will be back and will not wait for you to finish.” With this our team split up, Tom Bolland taking the lead with the initial layout that he had been working on for weeks running quickly out of sight, then Bez Burrows and Andy Firth establishing the pattern, with Yadgar Ali, James Haigh and Sparrow Braine making the final lines at the rear that the Land Rovers would later follow. The team was quickly dispersed beyond sight and only connected by the thread of familiar voices on our walkie talkies. Each part of the team were on there own hoping that the plan would work, and work in time.

Once the outline started to become established, we were joined by the Land Rovers assisted by Claire Jamieson from Sand In Your Eye to ensure co-ordination. We had fitted them with agricultural harrows normally used for raking fields. If they strayed outside our outline, they would cut a two-metre wide furrow in the sand. There was no margin for error. This was an element that we had only devised the day before. The Land Rover Experience team are a ‘can do’ operation and we soon developed a method that we were confident would work. By far the toughest aspect of the design would be the corners. These involved the right-hand vehicle of the formation making a pirouette in the sand. The turning circle of a Defender is what determined the overall width of the lines used to create the design. We had some very old vehicles out there with us, and they were pulling harrows that created huge friction. With its much narrower wheels, the 1951 Series I was having difficulties. What happened then was remarkable. The Land Rover Experience drivers let the tires down a little to get more traction. It worked, and the Series I pulled its weight as well as the rest, but it was the Land Rover spirit that stood out. They weren’t going to leave one behind.

Soon the Land Rovers were chomping at the heels of the Sand In Your Eye team. Low tide had passed and the sea was coming in. I was aware that the sea would start taking the image soon and so sent Andy Firth to the back wheel which would go first. “The sea is about 30 meters away!” he said. We did not have long. “Call the helicopter for its final pass!” When it arrived it flew so low and performed maneuvers that bordered on acrobatics, and then flew so high that it was a pinprick in the sky. The image was complete, we had done all we could and time had run out.

The strange thing about an operation like this is that, even when we had finished and parked up the Land Rovers and called the helicopter, we still didn’t know for sure if it had worked. It was just so ambitious and there was no way of telling from the ground what we had done. We later learnt that the helicopter had to fly right to the limit of its altitude threshold to capture the image, it was so vast, but then voices came through the walkie talkie yelling, “It’s worked, it’s worked!” After weeks of planning, we pulled off a very difficult operation in the space of four hours. That’s the spirit of the Defender. It is a vehicle that challenges all terrain, and that was what we were doing. We were taking up a challenge and we were having a go. That was the spirit of the people there on that day, and it’s the spirit of that machine.

Jamie Wardley

(editorial contributions from Nathaniel Handy)